At the beginning of the year I started writing a post for this newsletter, and then oh look a(nother) global round of layoffs. I tried to write the following week, and then oh look more layoffs. Then there were layoffs at my former company. Then they were (ongoing) at my current company.

Workplace adjustments. Worker reductions. Everything in passive voice. No one doing anything. Just the flow of capitalism, like the rise and fall of forests. Nature finding a way.

Here a type of proof: that it didn’t matter how hard you worked at anything. You could be let go. You would be let go.

Why? This was the obvious question. Thousands, hundreds of thousands, made redundant in less than a year. Is it a recession? The economy? War? Pandemic?

And god this is so boring and terrible but anyway - the layoffs are the system working as intended. The layoffs are a predictable, perhaps even necessary outcome of capitalism.

If I’ve lost you here, I understand. It’s exhausting. I’m exhausted.

Since I’m at least 15 years away from my stop-cutting-hair-and-move-into-the-forest phase, the only appropriate response seems to be

Radical thoughts from someone employed by Microsoft, a company with $100 billion in cash (truly, how is that even possible) which annually reduces its workforce by around 5%. Annually!

Why not start your own annual layoff tradition today?

No wonder everyone I talk to is plotting some kind of escape. Escape to what isn’t entirely clear, but escape from what is pretty obvious.

Maybe escape isn’t the right word. Some kind of hard shift (don’t say paradigm, don’t say paradigm). I’m told it’s called “quiet quitting”, as if George Orwell had never written Animal Farm.

As if Boxer died in vain.

Almost everyone at times has the sense that we are not using our technologies but are being used by them. Which is why, in the long run, as Jaron Lanier has pointed out, “the Turing test cuts both ways. You can’t tell if a machine has gotten smarter or if you’ve just lowered your own standards of intelligence to such a degree that the machine seems smart. If you can have a conversation with a simulated person presented by an AI program, can you tell how far you’ve let your sense of personhood degrade in order to make the illusion work for you?” We therefore come to imitate the distinctive stupidity of machines. If we are to be stupid, at least let our stupidity be human.

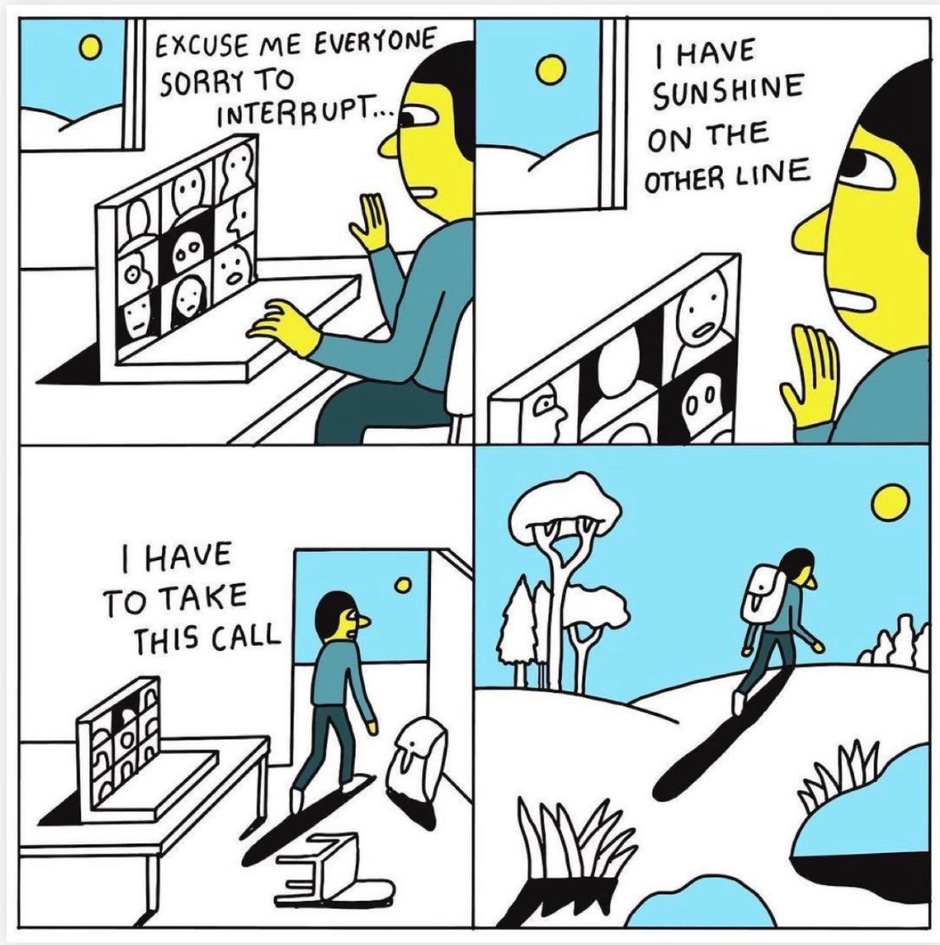

So maybe the first focal practice, the one that enables all the others, is simply this: to pause. To create intervals in our busyness. Maybe we will later fill those intervals with prayer, for instance, but just to create them is the first desideratum. Pause, and breathe — that alone declares our humanity and distinguishes us from our machines. The pilgrim pauses along the Way, and in that manner combats the laziness peculiar to a technologically accelerated age.

Two years ago to the day of this writing, I moved from London to Haarlem. I moved without M, and for 6 months the most common question I’d get asked was whether she’d be joining me “at some point”.

After she moved over, and we started living together for the first time, this was replaced by another question: where is she?

M and I have difference cadences and, for a couple, do a lot of things on our own, or, more specifically, without each other. It’s this “without each other” part that turned her existence into a bit of a running joke.

Before meeting M I was a do-everything-together guy, and very much a never-be-alone guy. Being alone felt like failure. Being in a relationship and NOT being at the same event felt like the world ending.

The shift not to just tolerating but actively seeking out solitude seemed completely natural, even as I was very aware of it. I have a weird bias where I think if I’m conscious of a change it must not actually be happening. How profound a change can it be if I notice it?

But it wasn’t until recently that I felt brave enough to wonder how it happened. (I have a related fear of never looking at a positive change too closely, lest it turn out to be a fabrication and immediately unravel.)

The first thing that happened is I no longer hated myself. That’s pretty important, because hating yourself makes it really hard to be with yourself. I’ve gone over how this happened before, so let me just say here that therapy is a very good thing.

The second thing is I picked up some hobbies. A lot of hobbies.

TIME

What I’ve learned from living with an artist is to have things you can make that can be completed within a human time scale. Human time scale means you can keep the entirety of it in your memory, which, unless you’re on some Beautiful Mind-style tip, means about a week. Better if it’s a day. Even better if it’s about an hour.

This is important because it means you can envision finishing the thing, and finishing a thing is the most important part of making a thing. It’s the absolute most important part. Starting and not finishing a lot of things is like being cut by many tiny little mind envelopes between your happiness fingers. It will make you feel bad.

Artists make things all the time. They’re always making things. And mostly, they’re finishing those things. Now look, I know we all have different ideas about art and what is art and etc. Let’s not go there right now. This is about having things you can make in human time scales.

Which is one of the reasons so many people started baking during the pandemic lockdowns. Because it’s soul-affirming to make a thing, and soul-affirminger to be able to eat that thing. You don’t even have to think about storage, the way you would with sculptures or paintings or macrame lampshades.

The reason this works is who you are when you’re making something is different from who you are when you’re just existing. Just existing is chill and sublime but also fraught with mind peril. Making is a distraction for sure, but a focused and enhancing distraction that leaves you, the distracted, full of purpose and accomplishment.

FOCUS

Because M knows roughly how long something will take for her to do it, when she sits down she can focus until its done.1 This sounds obvious to the point of banal, but if you’ve ever started a task and you had no idea how long it would take (taxes, cleaning our storage, writing a speech), you probably found your resolve waining from the very beginning.

Ever seen someone with an hourglass timer on their desk? If they weren’t boiling an egg, it’s likely they use the Pomodoro Technique. Pomodoro, which involves breaking tasks up into consistent blocks of time, has become a cursed artifact of the productivity age. But its benefits come from tricking the brain into thinking it knows how long something will take by enforcing that time. It doesn’t even matter if you actually “finish” a task in that time, because whatever you get done in the space is the finished task.2

Thom, I imagine someone might say who knows my name, don’t artists require creative freedom which only comes from just doing whatever for whatever length of time? And the answer is, yes! Boy howdy they do. We all do. And the world would be a wonderful place if our lives were a balance of focused work and unfettered exploration. I don’t even have a but for that—that’s a better world that we can probably have right now.

But like a kite flown on a seaside cliff, unfettered is only good for so long. Sometimes you need to rein that kite in, give it tension, to let it really soar. This is a very heavy metaphor I’m not afraid of using.

M works mostly in watercolour, which is a beautiful medium for blending and wildly frustrating for precision. (For me, not her. I’m pretty sure she could use watercolour for surgical guides.) The limitations of the medium inform the way her illustrations look, which in turn influences what she produces (I should say I’ve not checked any of this with her at all… this should probably be titled “What I think I’ve learned by living with an artist”),

When I struggle with writing, which is often, or drumming, or audio editing, or anything else my bastard vagrant of a mind has jumped to, I don’t try and power through. There’s a whole school of thought that says you should, but that’s someone else’s newsletter.

Instead, I introduce some sort of limitation to reduce the possibility space I’m working in. Either a time limit, or a selection of colours, or how long a clip can be. Taking away a vector limits one aspect of what I’m doing and in turn frees up that space for new thoughts to push it forward. You can always bring whatever you’ve taken away back.

The thing is, I knew all this before we started living together. It’s like creative life 101. I’ve probably read literally hundreds of posts advocating for focus and limitations and time management.

But until I saw M at her desk(s) every day, none of it meant anything to me. They might as well have been posters with kittens hanging off a ledge. I saw the messages, nodded my head, and proceeded not to do anything about it.

One of the best things about living with someone, which is to say one of the best things that can happen if you live with someone, is you’ll learn something you probably already knew. It will just sit in your head differently.

And that’s what I(think)’ve learned living with an artist.

Oh, and give each other space. Space is so important. Ok that’s it.

Bye.

Except when, uh, she can’t.

I should say I don’t use Pomodoro, or anything like it, but I get it. I think we could hang at a coffee shop and have a real nice time.